Monumental tombs were originally the privilege of the pharaohs. But things change when high officials become wealthy.

On March 7, 1920, an expedition from the Metropolitan Museum of Art was re-excavating tomb number 280 in Thebes – scientists were going to make some sketches. In the light of flashlights aimed at the crack in the wall, an amazing picture flashed before the scientists the entire life of the royal grandee Meketre. In the tomb of Meketre, the “chancellor and governor” of Mentuhotep I, was found the largest number of small wooden sculptures depicting servants engaged in a variety of activities. Such sculpture is characteristic of the Middle Kingdom period.

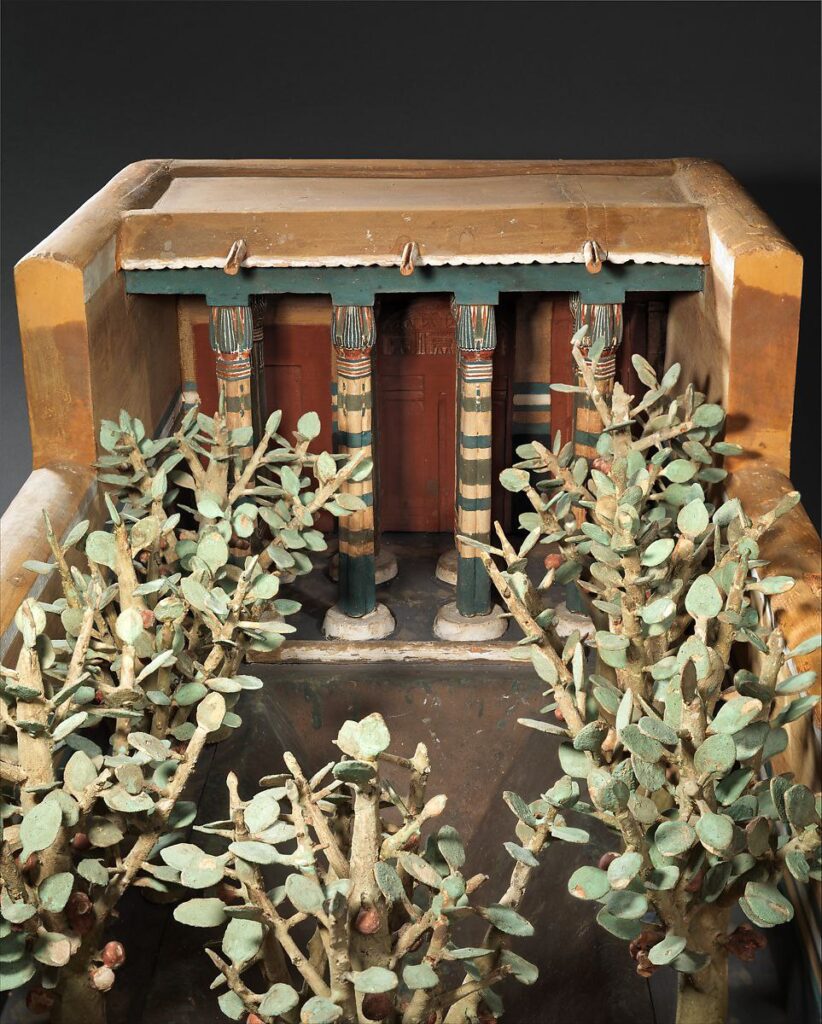

An official made an entire room at the back of his tomb with elaborately crafted models of sanded and painted wood, which were supposed to magically become his possessions in the afterlife. Among them were two models of houses with pools in the courtyards where the official could indulge in idle slumber, a bakery and a brewery, and a barn nearby.

Meketre would certainly not suffer from hunger in the afterlife.

All the artifacts were divided between the Metropolitan and the Cairo Museum. The boats carrying Mr. Meketre from the world of the living to the world of the dead went to the Metropolitan.

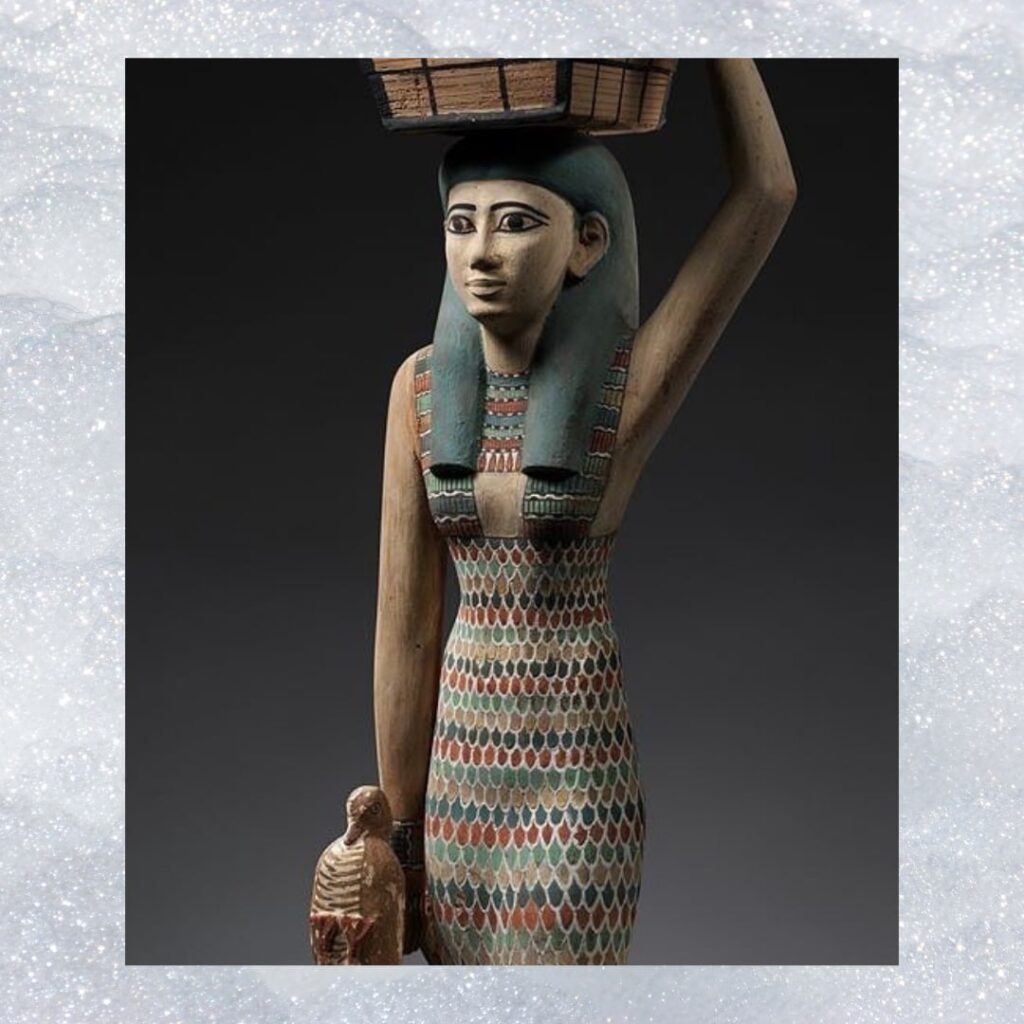

A statue of a priestess carrying gifts was also found there. A Rishi-style dress imitating the feathers of a bird, a basket of gifts on her head, a girl carrying a duck in her hand. The statue remained in the tomb and guarded it from encroachment.

Meketre was so rich that even his servants were buried with great luxury. For one servant alone 375 meters of linen cloth was spent. A kind of mummy cocoon was obtained. It is a rare case where the remains from the 21st century B.C. have come down to us in perfect condition.

" alt="Officials of ancient Egypt. Meketre" loading="lazy">

" alt="Officials of ancient Egypt. Meketre" loading="lazy">