Ancient Greece gave us the ideal man. Everything must be perfect in a person. The correct Greek features of the Hellenes are beautiful and almost perfect.

According to Pliny the Elder (an ancient Roman writer and polymath), the Greeks depicted people not “as they are, but as they appear to our senses. Any depiction of man must conform to the canon of Polycletus. What does this canon teach? The symmetry of the living body is primary. Beauty lies in the symmetry of the parts, that is, in the symmetry of the finger with the finger, the hand with the hand, the elbow with the elbow – and then all parts with all parts. Polycletus proved his word in deed – by building a statue in accordance with the instructions of his teachings. And, as we know, he called both this statue and this work his Canon. The beauty of the body lies in the symmetry of the parts.”

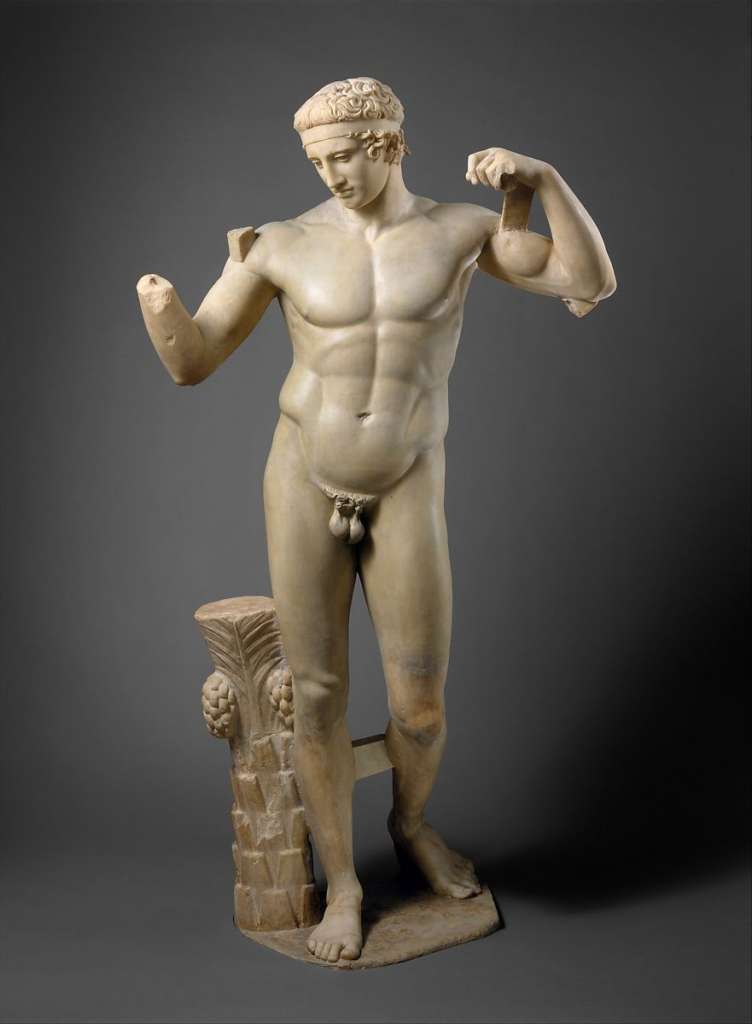

The museum’s collection contains Fragments of a marble statue of Diadoumenus (a young man tying a bandage around his head) c. AD 69-96. A copy of a work attributed to Polyclitus .

The head, arms and legs below the knees and the tree trunk are ancient. The remainder of the figure is a cast of a marble copy found at Delos and now preserved in the National Museum at Athens.

This statue represents a young man adorning his head with a bandage after winning an athletic contest. The original bronze sculpture probably stood in a sanctuary, such as Olympia or Delphi, where games were regularly held. The Greek sculptor Polycletus of Argos, who worked in the middle of the fifth century B.C., was one of the most famous artists of the ancient world. His figures were carefully designed with particular attention to body proportions and posture. The figure’s chest and pelvis are tilted in opposite directions, creating rhythmic contrasts in the torso that create an impression of organic vitality. The position of the legs, a balance between standing and walking, gives a sense of potential movement. This strictly calculated pose found in almost all of the works attributed to Polycletus,

Another interesting sculpture is the Marble Statue of a Wounded Amazon from the 1st-2nd century AD. A Roman copy.

The tibia and feet have been restored from casts taken from copies in Berlin and Copenhagen. Most of the right hand, the lower part of the column, and the pedestal are eighteenth-century marble restorations.

In Greek art, the Amazons, a mythical race of female warriors from Asia Minor, were often depicted fighting such heroes as Hercules, Achilles, and Theseus. This statue represents a refugee from battle who has lost her weapon and is bleeding from a wound under her right breast. Her chiton is unbuttoned on one shoulder and girded at the waist with her horse’s homemade bridle. Despite her plight, there is no sign of pain or fatigue on her face. She leans lightly on a pole to her left and gracefully places her right hand on her head in a gesture often used to indicate sleep or death. This emotional restraint was characteristic of classical art in the second half of the fifth century B.C.

The original statue probably stood on the grounds of the great temple of Artemis at Ephesus, on the coast of Asia Minor, where the Amazons had a legendary and cultic relationship with the goddess. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder described a contest held in the middle of the fifth century B.C. between five famous sculptors, including Phidias, Polyclitus, and Cresila, who were to make a statue of an Amazon for the temple. This type of statue is usually associated with this contest.

" alt="Ideal people of ancient Greece" loading="lazy">

" alt="Ideal people of ancient Greece" loading="lazy">